Morphological Description

Life History

Distribution

Habitat

Roost Sites and Roosting Patterns

Emergence and Flight Pattern

Foraging Behaviour

Echolocation Calls

Status and Protection |

|

|

Morphological Description

- Dorsal fur is light buff. Ventral fur is paler and may have a yellow tinge. There is an obvious division between the dorsal and ventral sides on the side of the neck.

- Fur is long and woolly or fluffy.

- Juveniles less than 12 months are greyish, with very young juveniles having a dark grey colouring.

- Ears are approximately three quarters of the length of the head and body and are longer than 28mm.

- Can be distinguished from the grey long-eared bat by the width of the tragus. The tragus of the brown long-eared bat is less than 5mm at its widest point.

- Can also be distinguished from the grey long-eared bat by the length of the thumb. The thumb of the brown long-eared bat is more than 6.5mm.

- Average weight (as given by Greenaway & Hutson, 1990) 6-12 g.

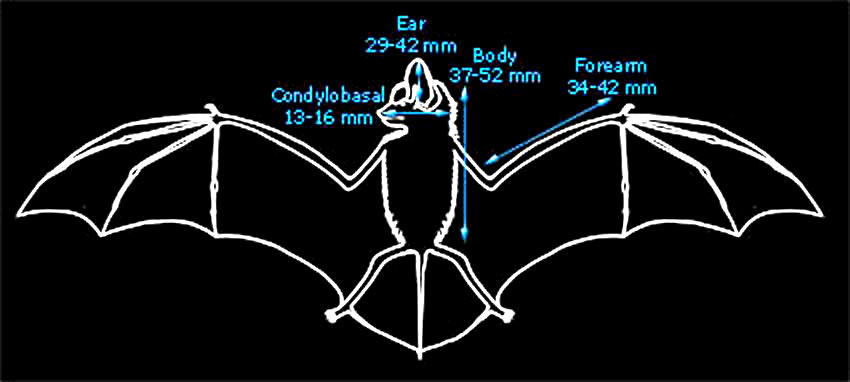

The diagram below gives important average body measurements for brown long-eared bats (Greenaway & Hutson, 1990).

|

Back to top |

Life History

- Mating occurs from October through to April.

- One young is born between mid-June and the end of July (Swift, 1991a).

- Maximum age recorded in Europe is 22 years but on average brown long-eared bats only live four and half years (Schober & Grimmberger, 1989) .

- A long term study of brown long-eared bats in Thetford forest found that the annual survival rates of female and male bats were 0.86 and 0.60 respectively (Boyd & Stebbings, 1989).

Back to top

|

Distribution |

|

|

|

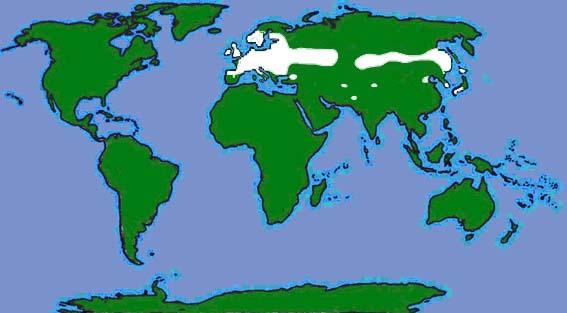

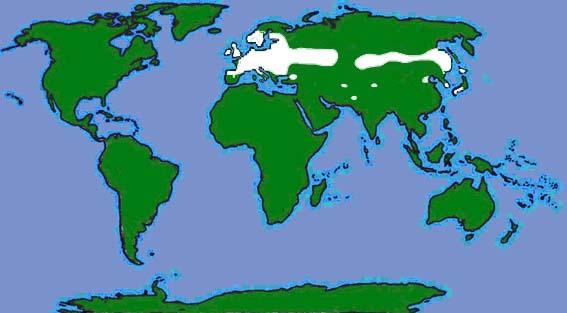

| The British and World distributions are shown by the white areas of the maps above (as given by Richardson, 2000 and Corbet & Harris, 1991 respectively). |

|

Found throughout Britain except in northern Scotland and offshore islands.

Back to top

|

Habitat |

|

• Open woodland including both deciduous and coniferous habitats.

• Sheltered valleys, parks and gardens.

• The photograph on the left shows a typical habitat of brown long-eared bats.

|

| Roost Sites and Patterns |

- Summer roost: Nursery roosts are found from May (Swift, 1991a) and usually consist of 10-30 individuals, although recordings of up to 200 individuals have been made (Greenaway & Hutson, 1990). Males are often present in nurseries. Roost in roofs of buildings either singly, in crevices and timber, or in clusters around chimneys and ridge ends.

- Winter roosts: Hibernate from November through to late March (Swift, 1991a). Roost in cooler regions of caves and similar environments. Brown long-eared bats are usually found in crevices but may be on the wall, sometimes hanging freely with the wings partially wrapped around the body. Usually roost singly or in very small clusters although they may roost with other bat species.

- Often found in bat boxes. May also occupy bird boxes and tree holes.

- Brown long-eared bats appear to select roosting sites according to the houses available. Preferences for older buildings with partitioned roofs which are within 0.5 km of woodland and water have been recorded. Brown long-eared bats also exhibit a preference for warmer houses for summer roost sites (Entwistle et al., 1997). Given that loss of roost sites is a major threat to British bats, this information should be considered when implementing conservation programs.

Back to top

|

Emergence and Flight Pattern |

- Usually only emerge in the dark, around an hour after sunset (Russ, 1999). May be active and make short flights within the roost prior to emergence. Return after 1-2 hours if suckling infants, if not return at dawn (Swift, 1991a).

- Median emergence time is 54 minutes after sunset (Jones & Rydell, 1994).

- Brown long-eared bats emerge relatively late at night (approximately 55 minutes after sunset) and remaining active throughout the night (Entwistle et al., 1996).

- Flight is slow, fluttering and low, generally close to vegetation. Often includes sweeping glides and hovering.

- Flight is very agile, even in very confined areas.

- The wings of juvenile brown long-eared bats grow faster than their body mass, altering their wing loading and hence their flying ability as they develop. At an age of 30 days juveniles have become more manoeuvrable and can fly more slowly at minimum power due to this allometric growth. This coincides with the time at which brown long-eared bats first leave their roost (McLean & Speakman, 2000).

Back to top

|

Foraging Behaviour |

Forages close to the roost in open woodland or parkland. Brown long-eared bats display a preference for deciduous woodland, and can glean insects from various surfaces (Entwistle et al., 1996).

Forages about 5-6m above the ground where there is thick vegetation (Swift, 1991a).

Foraging flight has short, twisting sections and includes upward scanning of vegetation.

The diet of brown long-eared bats consists almost exclusively of Lepidoptera, including many tympanate species (Vaughan, 1997).

A study by Sheil et al. (1991) on a population of brown long-eared bats in western Ireland showed that 42% of their diet was made up of insects which were probably gleaned from various surfaces such as foliage and the ground. The prey are thought to have been gleaned because they were insects that were diurnal or rarely flew, or non-flying arthropods. Ground-dwelling prey such as centipedes and the dipteran muscid Scatophaga stercoraria appeared to be common dietary components. The majority of prey items consumed by the brown long-eared bats were Diptera and Lepidoptera. Evidence of some very small prey items, such as aphids, was also found.

Large prey items are often consumed at a night perch.

Feeding sites are used and may be shared with individuals from the same roost (Entwistle et al., 1996).

Prey is probably detected by sight and sound using the large eyes and ears, not by echolocation. A study by Eklöf and Jones (2003) demonstrated the ability of the brown long-eared bat to visually detect prey. Under experimental conditions, brown long-eared bats showed a preference for situations where sonar and visual cues were available. However, visual cues were more important that sonar cues and the bats were unable to detect prey items using only sonar cues. Brown long-eared bats have relatively large eyes and ears and it is likely that visual information and passive listening allow this species to detect prey in cluttered environments.

Forages close to the roost in open woodland or parkland. Brown long-eared bats display a preference for deciduous woodland, and can glean insects from various surfaces (Entwistle et al., 1996).

Forages about 5-6m above the ground where there is thick vegetation (Swift, 1991a).

Foraging flight has short, twisting sections and includes upward scanning of vegetation.

The diet of brown long-eared bats consists almost exclusively of Lepidoptera, including many tympanate species (Vaughan, 1997).

A study by Sheil et al. (1991) on a population of brown long-eared bats in western Ireland showed that 42% of their diet was made up of insects which were probably gleaned from various surfaces such as foliage and the ground. The prey are thought to have been gleaned because they were insects that were diurnal or rarely flew, or non-flying arthropods. Ground-dwelling prey such as centipedes and the dipteran muscid Scatophaga stercoraria appeared to be common dietary components. The majority of prey items consumed by the brown long-eared bats were Diptera and Lepidoptera. Evidence of some very small prey items, such as aphids, was also found.

Large prey items are often consumed at a night perch.

Feeding sites are used and may be shared with individuals from the same roost (Entwistle et al., 1996).

Prey is probably detected by sight and sound using the large eyes and ears, not by echolocation. A study by Eklöf and Jones (2003) demonstrated the ability of the brown long-eared bat to visually detect prey. Under experimental conditions, brown long-eared bats showed a preference for situations where sonar and visual cues were available. However, visual cues were more important that sonar cues and the bats were unable to detect prey items using only sonar cues. Brown long-eared bats have relatively large eyes and ears and it is likely that visual information and passive listening allow this species to detect prey in cluttered environments.

|

|

|

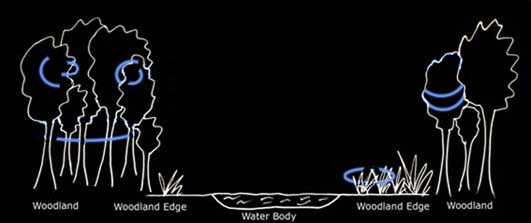

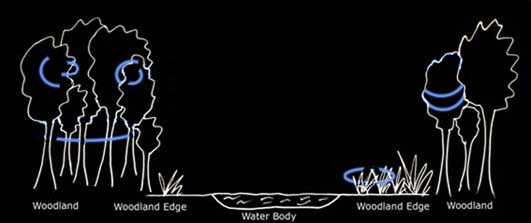

Marked in blue on the diagram above is a typical foraging path of brown long-eared bats (based on Russ, 1999).

Back to top

|

Echolocation Calls |

|

|

|

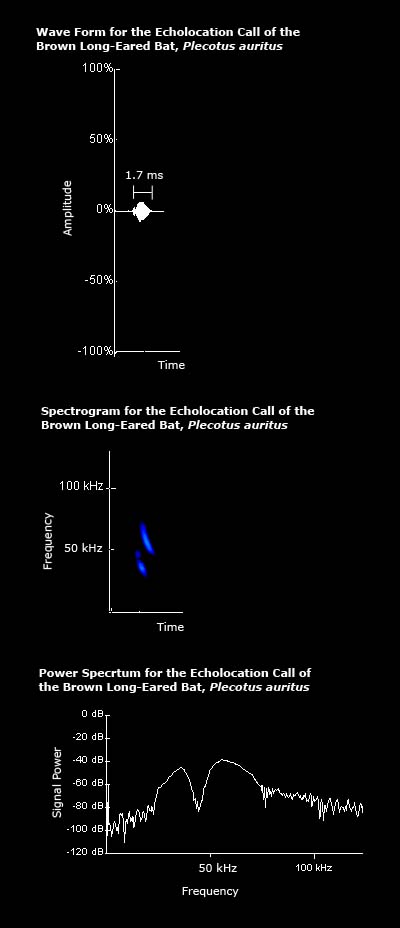

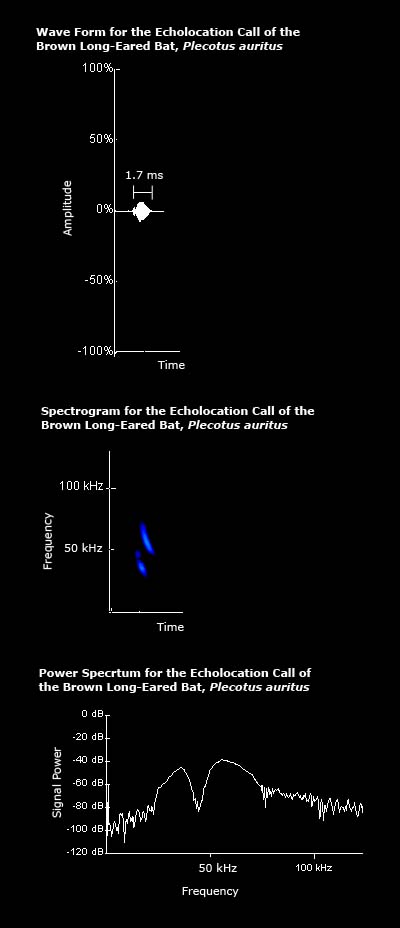

The echolocation call of brown long-eared bats is multi-harmonic (Russo & Jones, 2002). |

|

To listen to the call of the brown long-eared bat click here

Size of sound file: 2.77KB

|

|

| For details of how the echolocation calls were recorded click here. |

|

Average values for a brown long-eared bat echolocation call, as given by Vaughan et al. (1997), are listed below:

Interpulse interval: 104.2ms

Call duration: 1.7ms

Minimum frequency: 34.2kHz

Maximum frequency: 62.5kHz

The spectrogram on the left shows clear frequency modulation, with the call beginning at high frequency and ending at a lower frequency.

The power spectrum on the left shows that the maximum power of the call is at a frequency of approximately 40 kHz.

|

Back to top

|

|

| Status and Protection

- The British pre-breeding population was estimated at 200,000 in 1995 (155,000 in England , 17,500 in Wales and 27,500 in Scotland ) (Harris et al., 1995).

- Brown long-eared bats are at low risk of extinction worldwide (IUCN status, 2001).

- The brown long-eared bat is common in Britain although roost sites should still be protected and bat boxes erected.

- May be threatened by use of pesticides and timber treatments.

Back to top

|

© School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol 2005. Last modified 24th February 2005. © School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol 2005. Last modified 24th February 2005. |

© School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol 2005. Last modified 24th February 2005.

© School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol 2005. Last modified 24th February 2005.