Morphological Description

Life History

Distribution

Habitat

Roost Sites and Roosting Patterns

Emergence and Flight Pattern

Foraging Behaviour

Echolocation Calls

Status and Protection |

|

|

Morphological Description

- Dorsal fur is buff with darker tips. Older adults may be darker and reddish, females may be chestnut-brown. Ventral fur is paler and grey or yellowish-white.

- Juveniles are greyish in colour with the ventral fur being slightly paler.

- Fur is fluffy.

- Is easily identified by a horseshoe-shaped flap of skin surrounding the nostrils.

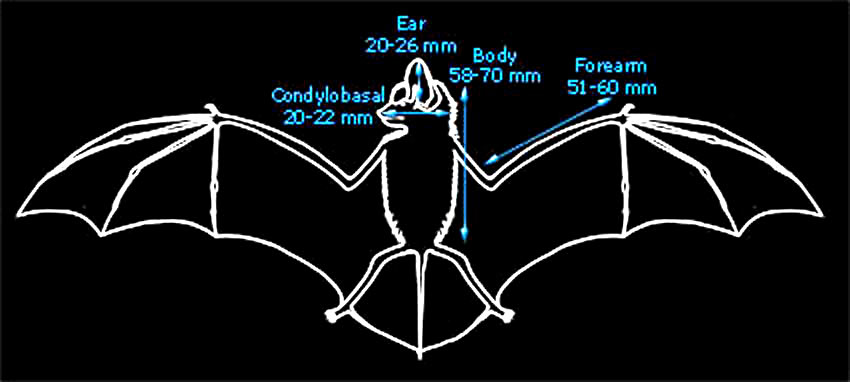

- Can be distinguished from the lesser horseshoe bat by size. The forearm of the greater horseshoe bat is longer than 45mm.

- Average weight (as given by Greenaway & Hutson, 1990) 13-34 g.

The diagram below gives important average body measurements for greater horseshoe bats (Greenaway & Hutson, 1990).

|

Back to top |

Life History

- Mate from autumn to spring but primarily in late September or October.

- Greater horseshoe bats have polygynous mating systems although Rossiter et al. (2000a) found that some females had offspring from the same male in separate years. Fidelity for either individuals or mating sites is likely to explain this behaviour, although it could also be due to sperm competition. Females mated with males from their natal colony as well as with males from outside the colony. Rossiter et al. (2000a) suggest that gene flow between colonies occurs through male and female dispersal during the mating period.

- One young is born between mid-June to the end of July, occasionally in August.

- The photograph on the left shows an adult greater horseshoe bat with an offspring.

- The timing of the births of greater horseshoe bats was studied by Ransome and McOwat (1994) for three colonies in south-west Wales and south-west England . Birth timing was significantly correlated with spring temperature, with young being born earlier after warmer springs. Cold springs and late births led to population declines and male-biased sex ratios at all three sites in 1986, although all the colonies recovered following subsequent warm springs. Births were approximately 18 days earlier when temperatures rose by 2°C.

- Park et al. (2002) studied torpor, arousal and activity in free-living greater horseshoe bats and found that arousal tends to be closely synchronized with dusk. As the temperature increased, the bats' torpor bout duration decreased, probably because of the increased rate of water loss.

- Maximum age recorded in Europe is 30 years (Schober & Grimmberger, 1989). Greater horseshoe bats have the longest recorded age of any European bat.

Back to top

|

Distribution |

|

|

|

| The British and World distributions are shown by the white areas of the maps above (as given by Richardson, 2000 and Corbet & Harris, 1991 respectively). |

|

- Limited to south-west England and south Wales, possibly by the need to feed in winter.

- Populations are localised and rare.

- The British population of greater horseshoe bats has declined and is now very fragmented. Analysis by Rossiter et al. (2000b) showed that Welsh populations of greater horseshoe bats are genetically isolated and have relatively low genetic variation.

Back to top

|

Habitat |

|

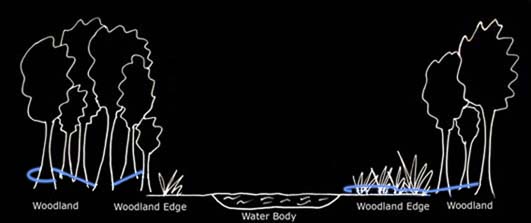

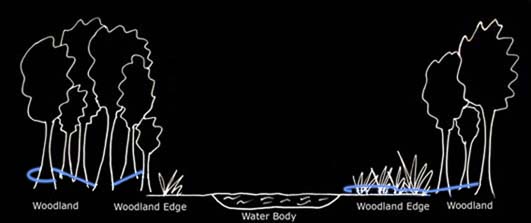

• Usually in areas with mixed deciduous woodland and grazing pastures on steep south-facing slopes.

• A study by Duvergé and Jones (1994) found that greater horseshoe bats preferred the following habitats (in descending order): pastures with cattle (either single/mixed stock), ancient semi-woodland and pastures with non-cattle stock. Woodlands and pasture close to woodland were used to a greater extent in spring and early summer while pasture was predominantly used in summer. Rides, footpaths, hedges and treelines were used by greater horseshoe bats when flying in these feeding areas. The bats were generally less than 2m away from these structures.

• Live in caves and similar environments in habitats with scrub and open trees away from human disturbance. Need a series of caves in order to have a variety of temperatures and air flow patterns.

• The photograph on the left shows a typical habitat of greater horseshoe bats.

|

| Roost Sites and Patterns |

- Summer roosts: Nursery roosts are found in attics in old buildings which can be accessed by uninterrupted flight and contain up to 200 females (Greenaway & Hutson, 1990). Greater horseshoe bats wrap their wings around their body and hang freely by the feet. Hang with their offspring either singly or in small groups. Adult males may be found in nursery roosts but leave when the young are born in mid summer. Males hold the same territory each year, and females return here annually.

- Winter roosts: Hibernate from September/October through to April in warmer regions of caves or similar environments. The exact timing of hibernation depends on the weather and the availability of food and breeding females tend to hibernate before other individuals. Horseshoe bats hang freely from the roof with males found either singly or in dense groups of up to 300 individuals with immature adults (Ransome, 1991a). Adult females tend to be solitary in winter. Hibernation is interrupted between once a day and once every 6-10 days (depending on the temperature and time of year) to feed near the cave entrance or change roost site. Females return to the same winter roost each year. May travel up to 10km in winter in search for roosts with the correct temperature and feeding sites (Ransome, 1991a).

- Different types of hibernacula are formed according to the age of individuals present in the roost. Single breeding males hold their own site in late summer, autumn and spring which is visited by up to eight females in September and October (Ransome, 1991a).

Back to top

|

Emergence and Flight Pattern |

- Emerges at dusk for about 30 minutes with an additional flight at dawn in spring (Ransome, 1991a). May use temporary resting sites or return to the roost between flights.

- Greater horseshoe bats' median emergence is 25 minutes after sunset (Jones & Rydell, 1994) and they return to the roost 5-30 minutes before sunrise (Duvergé and Jones, 1994).

- Flight is low and fluttering with brief glides.

- When hunting, flight is slow, with a maximum observed speed of 8.3m/s (Ransome, 1991a), and follows a regular path.

Back to top

|

Foraging Behaviour |

Hunts in open tree habitats such as pasture, parkland and hillsides, often by water.

The diet of greater horseshoe bats mainly consists of Lepidoptera and Coleoptera (Vaughan, 1997). Greater horseshoe bats forage using perch-hunting, hawking and gleaning strategies.

Duvergé and Jones (1994) found that the diet of greater horseshoe bats mainly consisted of Lepidoptera and Coleoptera (30-45%), followed by Diptera (10-20%) and Hymenoptera (5-10%), although these proportions change seasonally.

Drinks while hovering or during low-level flight.

Winter foraging depends on the weather and prey availability.

The photograph on the left shows cockchafer remains found beneath a feeding perch of greater horseshoe bats.

Hunts in open tree habitats such as pasture, parkland and hillsides, often by water.

The diet of greater horseshoe bats mainly consists of Lepidoptera and Coleoptera (Vaughan, 1997). Greater horseshoe bats forage using perch-hunting, hawking and gleaning strategies.

Duvergé and Jones (1994) found that the diet of greater horseshoe bats mainly consisted of Lepidoptera and Coleoptera (30-45%), followed by Diptera (10-20%) and Hymenoptera (5-10%), although these proportions change seasonally.

Drinks while hovering or during low-level flight.

Winter foraging depends on the weather and prey availability.

The photograph on the left shows cockchafer remains found beneath a feeding perch of greater horseshoe bats.

|

|

|

Marked in blue on the diagram above is a typical foraging path of greater horseshoe bats (based on Russ, 1999).

Back to top

|

Echolocation Calls |

|

|

|

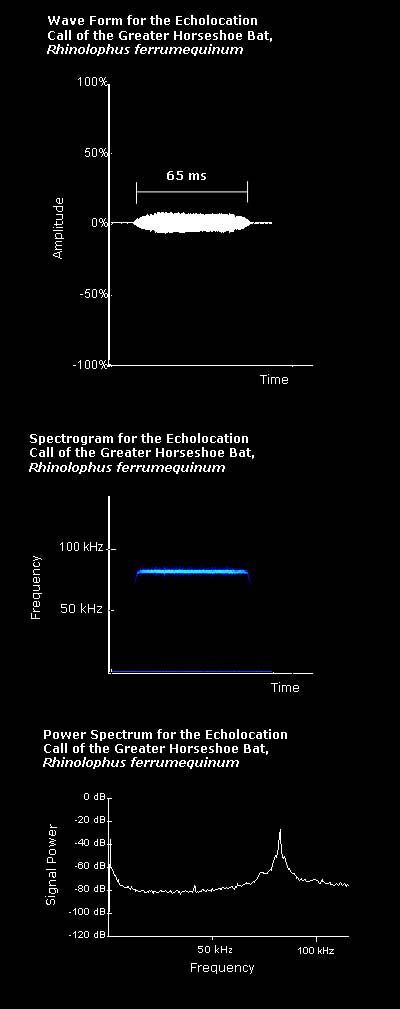

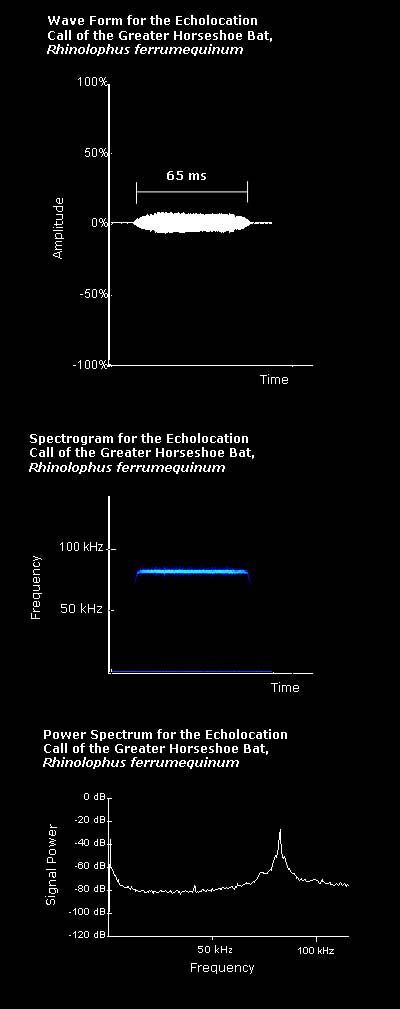

The echolocation call of greater horseshoe bats is constant frequency with a frequency modulated component at the start and end. |

|

To listen to the call of the greater horseshoe bat click here

Size of sound file: 76.9 KB

|

|

| For details of how the echolocation calls were recorded click here. |

|

Average values for a greater horseshoe bat echolocation call, as given by Vaughan et al. (1997), are listed below:

Interpulse interval: 83 ms

Call duration: 49 ms

Minimum frequency: 69 kHz

Maximum frequency: N/A

The power spectrum on the left shows that the maximum power of the call is at a frequency of approximately 82 kHz.

|

Back to top

|

|

| Status and Protection

• The British pre-breeding population was estimated at 4000 in 1995 (3650 in England, 350 in Wales), but may actually be closer to 6600 (Harris et al., 1995).

• Greater horseshoe bats are on the verge of becoming a threatened species worldwide (IUCN status, 2001).

• Protection of winter roosts, nursery roosts and prey populations is necessary.

• The photograph on the left shows greater horseshoe bats in an attic.

• The greater horseshoe bat is listed in the UK Biodiversity Action Plan and is one of the rarest mammal species in the United Kingdom . The main threats facing greater horseshoe bats are the loss of roost sites and foraging areas (Duvergé & Jones, 2003)

• Roost sites may be lost as buildings (especially those associated with farms) are converted or become derelict. A range of buildings are needed for activities such as mating, breeding and night roosting. Greater horseshoe bats may also be at risk from chemicals used within roost sites, for example, remedial timber treatment (Duvergé & Jones, 2003).

• Foraging habitats may be lost through changes in land-use or farming practices or the removal of linear features such as hedgerows. Greater horseshoe bats may also be at risk from chemicals used on nearby vegetation, if they either come into contact with that vegetation or consume insects that have been sprayed or eaten sprayed food. There is some indication that the use of avermectin worming compounds may impact on bat activity via its effects on insects in the cowpat community (Duvergé & Jones, 2003).

• In order to protect greater horseshoe bat colonies, Duvergé & Jones (2003) suggest that permanently grazed pastures should not be ploughed and used from arable crops and that woodland and hedgerows should be retained. Hedegrows should be approximately 4m high and 2-3m wide and should not be intensively trimmed. Important habitats within 4km of roost sites should be preserved.

• Duvergé and Jones (1994) found that a range of high-quality foraging areas is essential for the survival of greater horseshoe bats. They therefore suggest the conservation of ancient semi-natural, deciduous and mixed woodlands. Pasture with cattle grazing is also very important (Duvergé & Jones, 1994). Thick hedgerows, treelines or fences along the field boundaries should be maintained as prey tends to accumulate on the leeward side of these structures and because they provide perch sites and travel routes for the bats. Duvergé and Jones (1994) suggest that key habitats within 4km of a greater horseshoe roost site are maintained or improved.

Back to top

|

© School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol 2005. Last modified 24th February 2005. © School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol 2005. Last modified 24th February 2005. |

© School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol 2005. Last modified 24th February 2005.

© School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol 2005. Last modified 24th February 2005.